MADI Students Design Innovative Solutions for Toyota Mobility Foundation’s ‘Mobility for All’ Mission

Students from SMU’s M.A. in Design and Innovation program conceptualized innovative design solutions to solve real-world mobility barriers for those with lower limb differences

Darius Harris is an artist and military man.

When he learned the group project for his M.A. in Design and Innovation (MADI) class at SMU supported by both the Lyle School of Engineering and the Meadows School of the Arts would focus on solutions for those with lower limb differences, he was thrilled to combine two important interests – creative design and assistance for military veterans – and knew exactly who to interview for research.

“I called a U.S. Air Force chaplain who could give our group perspective and inspiration from his experience,” Harris said. “It’s so important to understand the real-world impact of how your design can help communities.”

—Thinking grad school? Think SMU Lyle. Learn about our M.A. in Design and Innovation. —

Toyota Mobility Foundation approached the MADI program with a rigorous design challenge: How might we make it easier for those with lower limb differences to engage in an active lifestyle? The foundation partners with innovators, thinkers, and creators from a variety of backgrounds to provide solutions for mobility challenges, with the underlying philosophy: “When people are free to move, they can broaden their horizons and fully realize their potential.”

The MADI program operates under a similar philosophy. A hospital social worker, an event coordinator, and a health technology developer were among the students in Harris’ class, which welcomes applicants from diverse backgrounds with a desire to learn design and effect change. The program teaches the Human-Centered Design process to create meaningful solutions rooted in research.

“The program plays on the strengths you have in your unique background and utilizes design thinking in spaces that may not currently utilize it,” Harris said. “Whether it’s social impact, physical design, digital design, or graphic design, the Human-Centered Design process is invaluable for all areas.”

Human-Centered Design puts people and qualitative methods at the center of the development process. Students in the MADI program collaborate with real-world clients inside and outside of the classroom. Since its inception in 2015, they’ve worked with a variety of partners including Southwest Airlines, Dallas Police Department, Dallas Mavericks, Volunteer Now, and this fall will be working with Big Thought.

The MADI program recently launched a new Product Design and Innovation concentration that is being led by Dr. Seth Orsborn, Professor and Director of the Deason Innovation Gym. The Innovation and Design Attitude class is the first in a three-course series focused on the problem solving and design of physical products.

“Product Design and Innovation connects with entrepreneurs, start-ups, small businesses, and multi-nationals to design innovations that meet the needs, wants, and desires of users,” Orsborn said. “These are great opportunities to implement classroom learnings while collaborating with professionals and producing real, impactful results.”

As we looked deeper and listened better, we gained a greater respect for the journeys we explored. I think more engagement in the design process leads to a clearer understanding of one another, and hopefully, more humane solutions.

Lauren Kelly, graduate student in SMU Lyle’s MADI program

Lauren Kelly, MADI student with an undergraduate degree in Global Studies from St. Edward’s University, said she was excited to participate in impactful research for local, national, and multi-national companies addressing real-world issues like mobility. Facilitated by The Foundation and ToyotAbility, the class interviewed Paralympic athletes Jarryd Wallace and Amy Purdy who shared the importance of medical support and community in their journeys.

“The best part of research is hearing from the users, since they are the true experts on their experience,” she said. “We got to learn from creators, users, and providers at incredible organizations like ToyotAbility, Prosfit, Scottish Rite, and Adaptive Training Foundation. The project really opened doors to continued research and collaborative work on this important issue. The program offers so many amazing courses to practice, improve, and apply our design skills so we can be better design leaders.

“As we looked deeper and listened better, we gained a greater respect for the journeys we explored. I think more engagement in the design process leads to a clearer understanding of one another, and hopefully, more humane solutions.”

At the culmination of their research and interviews, the groups presented three design concepts to Toyota Mobility Foundation:

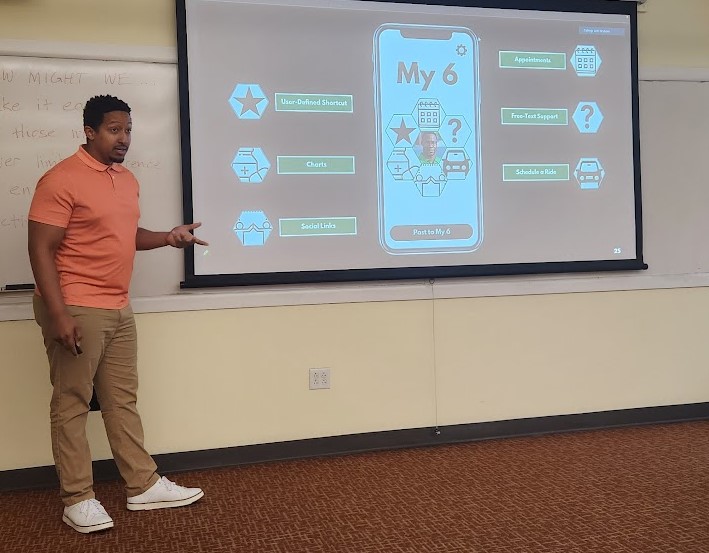

- My6 – an app for military veteran amputees that provides care navigation, appointment scheduling, medical charts, support, rideshare requests and social interaction in one hub.

- SensMate – a socket sleeve for teenage amputees that uses AI and data to recommend which option is best for comfortability and activity level.

- AIRecover – a socket sleeve for diabetic amputees that uses AI and sensors to give feedback on recovery exercises and disease management through an app.

Darius Harris presents his group’s app design to Toyota Mobility Foundation.

“The MADI program really deprograms the single-solution mindset prevalent in most engineering majors,” said McKenna Pape, a project manager for healthcare technology design. “It’s really easy to get blinders on and only see one way. This program helps get the creativity muscle moving that I felt I was missing.”

Benjamin Johnston-Leamon, a hospital social worker and MADI student, said MADI’s emphasis on industry connections and understanding how real-world engineers implement solutions has already helped him implement policy changes and scale them in his current job.

“Any solution, whether it’s sensors that help people with diabetes manage their own experience or working with veterans, has to be something that takes into account the very real, very valid account of experience,” he said. “If we ever get away from that, who are we designing for or engineering for? Who is your user and how will this help them? Keeping that in mind every step of the way and constantly going back to those questions in any field is so impactful.”

William Chernicoff, the Toyota Mobility Foundation’s sponsor and collaborator, applauded the students’ projects, calling them “actionable and valuable to the community,” and will continue working with the MADI program and its students over the summer to conduct further research and take the next step towards potentially bringing the ideas to life.

“The MADI program offers the chance to practice design and bring innovative solutions to our society’s biggest needs, wants, and desires,” Kelly said. “It’s interdisciplinary, incorporating business, engineering, and the arts, which I think is increasingly important in the modern age. The leaders and faculty involved are an invaluable resource offering top-tier design expertise and serving as inspiring, genuine, changemakers for the heart of Dallas.”

About the Bobby Lyle School of Engineering

SMU's Lyle School of Engineering thrives on innovation that transcends traditional boundaries. We strongly believe in the power of externally funded, industry-supported research to drive progress and provide exceptional students with valuable industry insights. Our mission is to lead the way in digital transformation within engineering education, all while ensuring that every student graduates as a confident leader. Founded in 1925, SMU Lyle is one of the oldest engineering schools in the Southwest, offering undergraduate and graduate programs, including master’s and doctoral degrees.

About SMU

SMU is the nationally ranked global research university in the dynamic city of Dallas. SMU’s alumni, faculty and nearly 12,000 students in eight degree-granting schools demonstrate an entrepreneurial spirit as they lead change in their professions, community and the world.