Placing neighborhoods in focus

Researchers combined street-level investigations with SMU’s supercomputer power to reveal infrastructure deserts. Their study lays the groundwork for improving neighborhoods.

Residents of a neglected corner of southeast Dallas daily navigate crumbling sidewalks, pothole-riddled streets and neglected intersections. Few trees shade their streets, and the lack of access to basic services like internet, health care and grocery stores isolate them within a thriving city. Like residents of 61 other Dallas neighborhoods, they live in an infrastructure desert.

What are infrastructure deserts? Why do they matter?

Those two questions get to the heart of a multiyear research project led by SMU’s Barbara Minsker, a nationally recognized expert in environmental and infrastructure systems analysis.

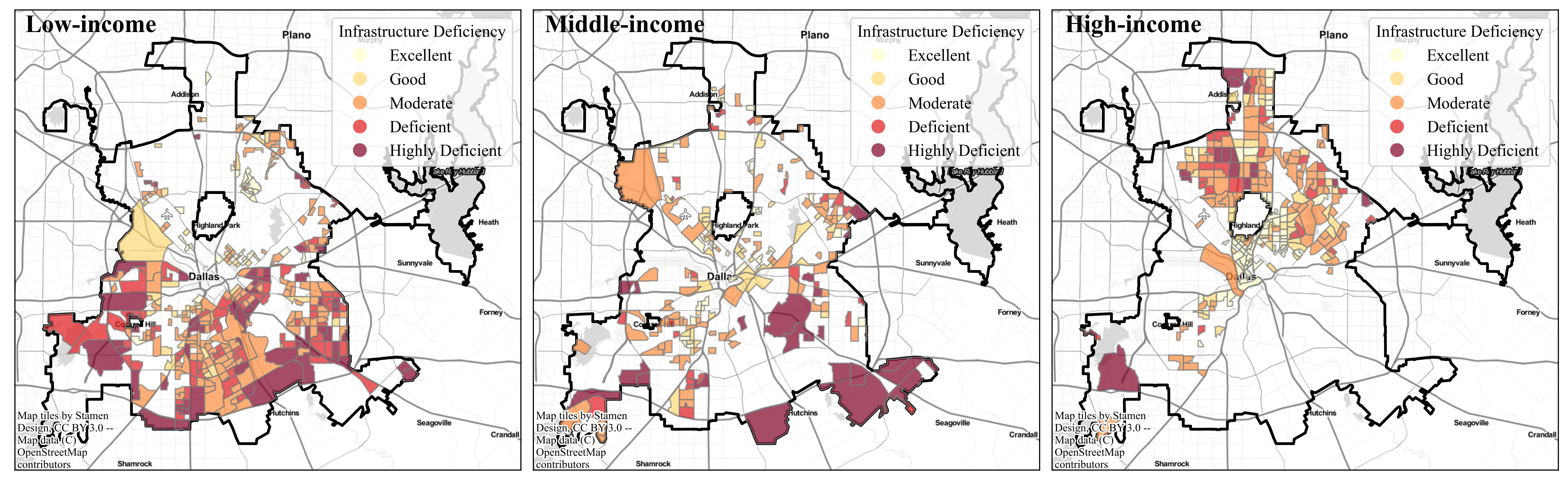

To find answers, Zheng Li, a Ph.D. student in civil and environmental engineering, and other team members created a computer framework with the ability to assess, at census-block level, 12 types of infrastructure. Neighborhoods were evaluated and compared by infrastructure deficiency, household income and ethnicity.

“This framework enables us to collect data from a huge variety of sources, then analyze the patterns that emerge to discover new information that can be used by scientists, policymakers and residents to improve their neighborhoods,” Li says.

More than 20 undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, staff and community members contributed to the research.

The multidisciplinary team included co-authors Janille Smith-Colin, assistant professor, and Jessie Zarazaga, clinical associate professor and Hunt Institute Fellow, both from the civil and environmental engineering department in the Lyle School of Engineering; and Xinlei Wang, statistical science professor in Dedman College of Humanities and Sciences.

SMU’s supercomputer was put to work mining huge public datasets, including 5 terabytes of images from the city of Dallas.

Undergraduate and graduate researchers used drones, smart phone applications and artificial intelligence, as well as their own feet-on-the-ground observations, to gather information supplementing the public data. They also held brainstorming sessions to learn what residents felt were their communities’ greatest infrastructure needs.

Nearly 800 Dallas city neighborhoods were rated on streets, sidewalks, pavements, crosswalks, noise walls, street tree canopy, bike and pedestrian trails and community gathering places as well as access to public transportation, hospital or medical services, banks and financial services and food. Each neighborhood was given a grade of excellent, good, moderate, deficient or highly deficient.

The data led researchers to identify 62 Dallas neighborhoods as infrastructure deserts: low-income areas highly deficient in infrastructure that creates a safe, functional and economically viable area in which to live. Known as infrastructure deserts, most of the neighborhoods are located in the southern part of the city and home to primarily low-income, Black and Hispanic residents.

Often infrastructure funding is used for major investments, like freeways or airports. This study shows the importance of funding for smaller scale infrastructure at the neighborhood level.

— Barbara Minsker, Bobby B. Lyle Endowed Professor of Leadership and Global Entrepreneurship

Infrastructure deficiencies can increase vulnerability to major shocks, like a pandemic or severe weather, Minsker says.

“We saw poor access to medical care and public transit as major problems affecting access to health care during COVID. Lack of Internet access interrupted the education of thousands of school children,” she says.

Related links

There were also subtler effects, she says. “The lack of community gathering spaces reduces community support, which affects resilience and health. Lack of access to parks and trails can decrease mental and physical health, particularly when COVID prevents many other activities.”

Minsker’s work is supported by a five-year $584,000 National Science Foundation grant which funds the development of open-source data management software called Clowder.

The project was an opportunity for students to plunge into the basics of data science, Minsker says. “It’s equipping our civil and environmental engineering students with data literacy and experience in working with algorithms that they’ll take into the workplace,” she says.

For Minsker, this project tapped into her passion for improving community and ecosystem health and well-being through engineering. That’s also a primary objective of SMU’s Hunt Institute for Engineering and Humanity, where Minsker serves as a senior fellow.

The long-term plan is to use the research framework they’ve created to study other cities, such as New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.