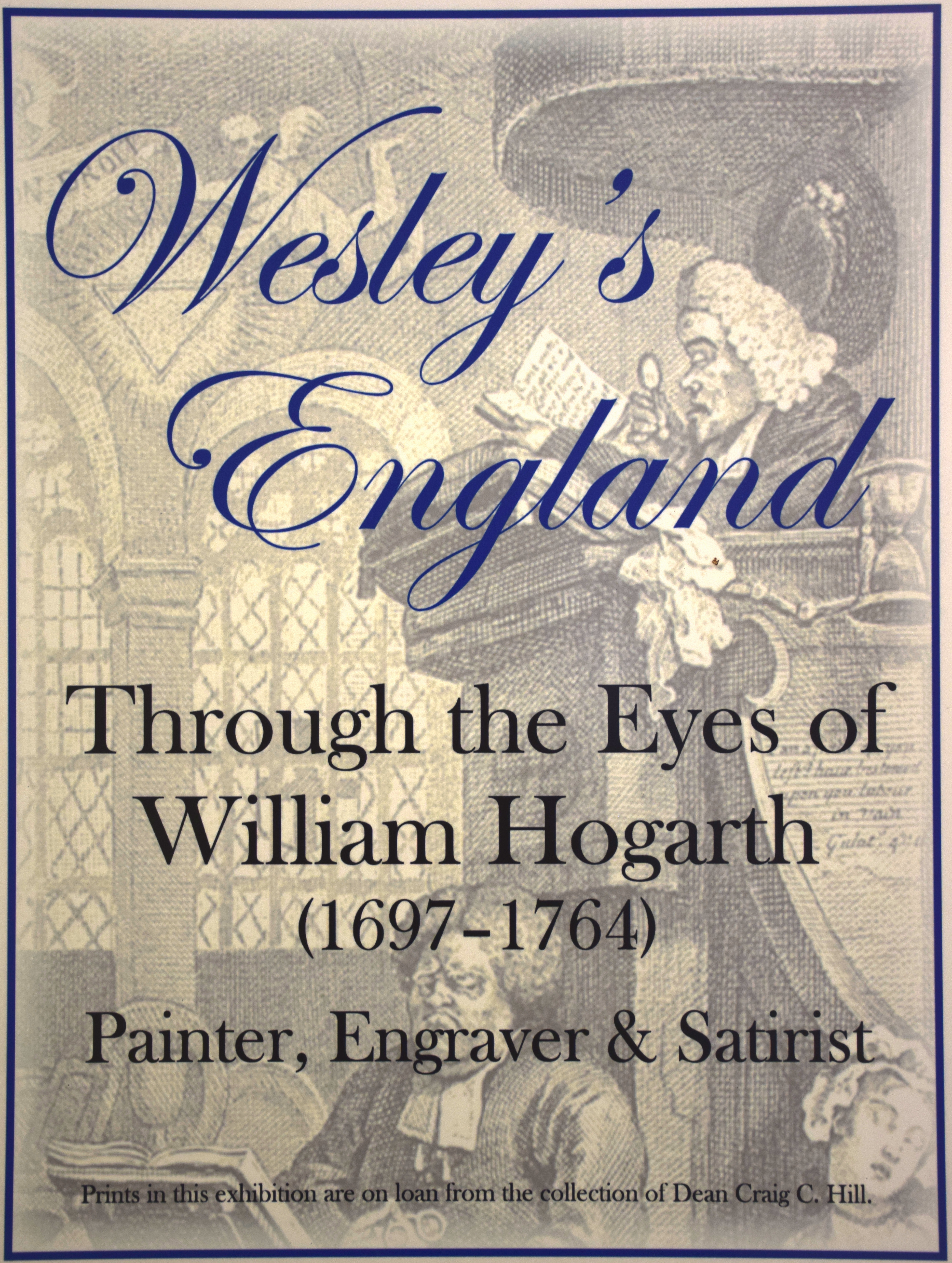

Hogarth Exhibition Provides Glimpse of Wesley’s England

Print collection, on display in the Elizabeth Perkins Prothro Hall, shows artist’s satirical look at 18th century Britain.

As a seminary student, Dean Craig Hill developed a passion for centuries-old English prints. Now, that youthful obsession is benefiting students, faculty and visitors at Perkins School of Theology.

Hill has loaned more than a dozen prints by English artist William Hogarth (1697 – 1764) for exhibition in Elizabeth Perkins Prothro Hall, where they’re offering visitors a unique and revealing glimpse into the time and place where Methodism began.

“The prints give a little picture of what 18th century British life was like, and what some of the challenges to Methodism were,” he said. “They’re social artifacts -- the popular visual representation of that period.”

Hill’s interest was first sparked at an auction at the church he attended while on a student internship at Oxford. He placed a bid on a 200-year-old topographical print – and won.

“I discovered that I could own something that was lovely, decorative and historic, for just a few pounds,” he said. “I was hooked.”

As Hill returned to England to live multiple times over the years, he continued to collect hundreds of prints, with a particular focus on prints by Hogarth, an English painter, printmaker and satirist, a contemporary of John Wesley, and possibly the most significant artist of his generation.

“Hogarth’s career overlapped significantly with that of Wesley, and it’s a very interesting time period,” Hill said. “This was the time of the rise of the middle class. Middle class people were coming into their own, wanting to be educated, and having their own set of morals.”

Wesley’s Contemporary

Around the time Hill arrived at Perkins in 2016, the Art & Design Committee of Perkins Executive Board was looking for ways to enhance the environment in Prothro.

“When we learned about Dean Hill’s collection, of course we hopped all over it,” said committee member Gay Solomon, adding that Hill had loaned prints for a similar exhibition at Duke University Divinity School, where he taught before coming to Perkins.

Now, the Hogarth prints are adding beauty to the environment at Prothro as well as a rich source of context for students of Wesleyan history.

Prior to Hogarth’s time, most art was commissioned by the wealthy and portrayed classical stories and themes, or the wealthy patrons themselves. Hogarth’s prints, however, reflected contemporary life and everyday concerns. In their broad appeal and interest, the prints were much like the popular TV series of today. Ordinary people purchased the prints by subscription, and hung them on the walls of their homes.

“There’s also a broad social consciousness in Hogarth’s prints that you don’t typically see in prior art,” Hill added. “Hogarth is satirical, but he’s not cynical. He doesn’t hate the middle class, but he targets their foibles.”

A careful viewer can easily spend an hour or two with each Hogarth print. Each tells a story, with myriad details reflecting class, religion and values of the time. Often, Hogarth pokes fun.

Two prints, in particular, portray religious life during Wesley’s time. “The Sleeping Congregation” (1736) shows an Anglican worship service that reveals the decadence and irrelevance of the church at the time. The church clerk ogles a buxom maiden; the preacher’s sermon text, “Come unto me all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest,” makes a sly reference to the pews full of sleeping worshippers.

By contrast, “Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism” (1762) depicts a rowdy gathering of Methodists, caught up in religious fervor that, in Hogarth’s view, is enthusiastic but shallow. A thermometer implies crowd’s religion is only lukewarm; nearby, an alms box remains untouched – there’s a spider’s web inside -- suggesting a lack of genuine interest in caring for the poor.

“Hogarth is critiquing the two extremes of religious people at the time – whether they’re falling asleep, or caught up in artificial excitement,” Hill said.

Solomon, who is also a former member of the Dallas Museum of Art Board of Trustees, said the prints still speak to contemporary people of faith.

“Hogarth shows us that, even though we are trying to follow Jesus’ way, it is human nature to try to aggrandize our own self-image and importance,” she said. “

Moral Instruction

Among the most famous prints in the exhibition are “Beer Street” and “Gin Lane” (1733), a bit of political propaganda created by Hogarth in support of a bill before Parliament to restrict the import of gin. In “Beer Street,” citizens are healthy and industrious; the area is prosperous, and buildings are under construction. By contrast, “Gin Lane” paints a picture of destitution and debauchery; there’s a man who has hung himself, a mother who neglects her baby, a gin seller who profits from the misery.

Many of Hogarth’s most famous works were series of prints, which he called “progresses,” offering moral instruction. For the exhibition, Hill selected a progress of 12 prints, entitled “Industry and Idleness” (1747). The morality tale contrasts the lives of two fictional characters, Francis Goodchild and Tom Idle. In the first print of the series, the two are both apprentices, working side-by-side in a silk-weaving operation in London. Goodchild strives diligently; Idle is asleep. From there, the two apprentices’ paths diverge. Goodchild attends church, rises in the business, marries the boss’s daughter, and ultimately becomes a magistrate. Idle, however, gambles in the churchyard, runs off to sea, and consorts with a prostitute.

Ultimately, the two are reunited when Idle is brought before Goodchild in a trial. In the final two prints of the series, Idle faces execution as Goodchild becomes Lord Mayor of London.

The tale may seem heavy-handed to modern audiences, but Hill said it reflects 18th century concerns about choices, consequences and their ultimate effects on the poor and most vulnerable.

“We might object that Hogarth is overly simplistic, but I don’t know anyone of that time who shows more compassion to those who are chewed up by the machine of the day, whether by unfair politics or bad behavior,” Hill said.

And those broader themes do still resonate, said Will Willimon, a retired United Methodist bishop and Professor of the Practice of Christian Ministry at Duke. While the prints were displayed at Duke, Willimon used them as teaching tools. Students identified social ills depicted in Hogarth’s prints, and then considered whether they were still relevant.

“They said that every single social evil of Hogarth’s day was still alive in our day,” Willimon said. “Would that we could be as creative in our truth-telling as Hogarth!”

Mary Jacobs, former staff writer for The United Methodist Reporter, is a freelance writer in Dallas.